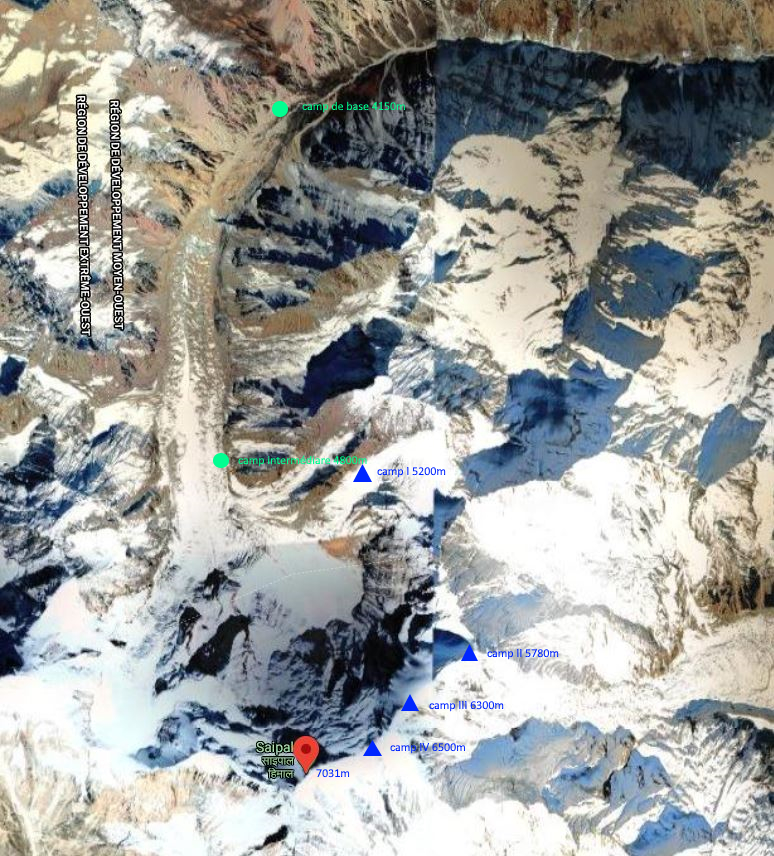

New route at Saipal

Expedition by the Geneva section of the SAC to Saipal

Kathmandu and approach walk

19th September 1990

Arrival in Kathmandu.

We are welcomed by Tensing, who introduces us to the sherpas and other members of the expedition, as well as the equipment for the trek to base camp.

Passing by a temple, we were blessed with a red mark on our foreheads called « the Tika« .

21st September

Reception and repair of the compression bag.

Our colonial-style hotel is set amidst rice paddies,

10 minutes from the bazaar by rickshaw.

22nd September

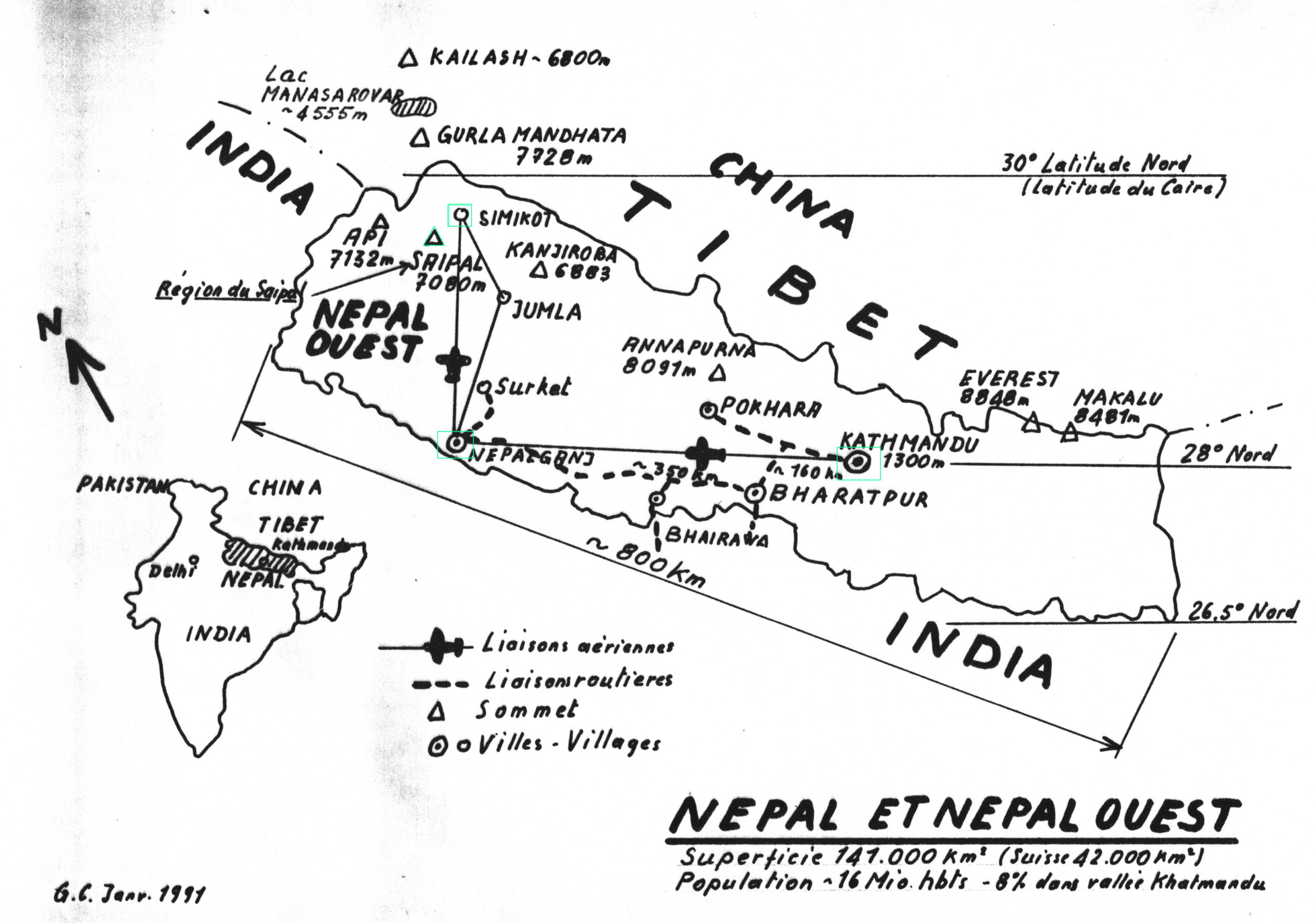

Departure for Nepalganj at 12:30 on a Twin Otter, after a picnic at the airport refreshment bar.

We flew to an altitude of 3,300 m., with views of Annapurna and Dhaulagiri. Perfect landing at Nepalganj (150 m.). It’s hot (35°C) and very humid.

Rice paddies as far as the eye can see and big muddy rivers. A typically Indian town.

The locals are busy preparing for the « Dashain » festival.

23rd September

Departure for Simikot. We wake up at 4.15am and take off at 6.45am. We fly at 4115 m. through the clouds.

Simikot is a town in the mountains of the north-western Nepalese Himalayas, at an altitude of 2,910 metres.

The pilot had trouble making out the track.

On the 4th run… at last some light on the 500m dirt track.

Unloading. The whole village is there… it’s a party!

Most of the equipment had already arrived the day before, along with a sherpa and a kitchen assistant.

Simikot

The kitchen is smoking. A large plastic sheet is spread out to welcome us with the traditional tea.

Our tents are assembled. The seams are waterproofed and the zips are soaped to improve their operation.

Dinner is served in the mess tent by the light of a paraffin lamp.

24th September

Breakfast served by the Nepalese staff at the entrance to the tent. I accompany Alex to the village fountain for a wash and a few ablutions. In the afternoon, we visit Simikot and walk to a « Chörten » (one of the symbols of the Buddhist religion). The long-awaited yaks have still not arrived.

25th September

Wake-up call at 06:30. The yaks are here. We pack up our tents and set off.

At the sight of the disorganised mess, Georges runs off followed by Geneviève, our nurse. I soon followed.

A very steep descent to the bottom of the valley. We take the lower path, the yaks the upper one, which is longer but easier.

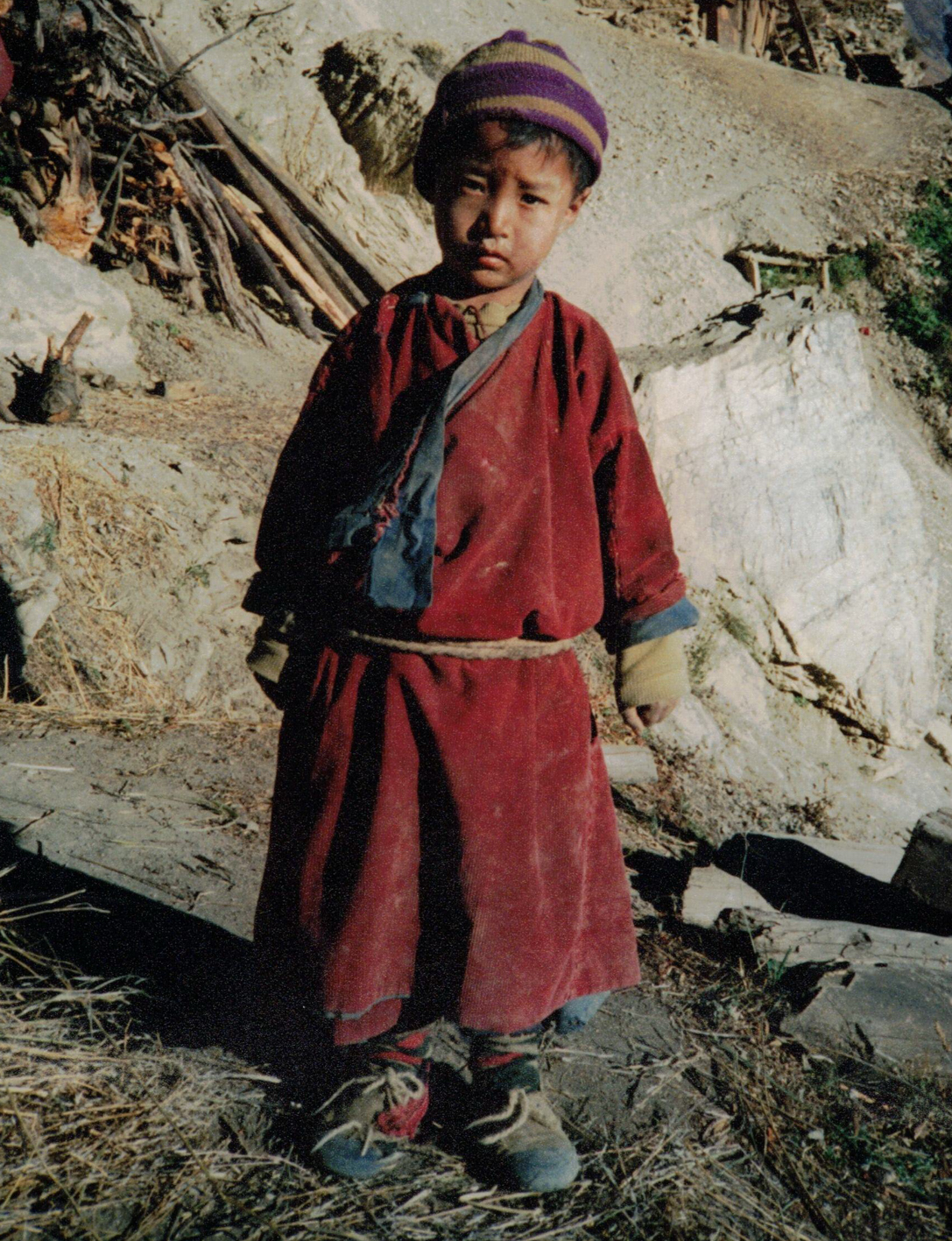

As we drive through a hamlet, Geneviève gives a little girl the rest of her picnic.

The mother offers us delicious potatoes in their field dresses.

At Dara Pori, we pass a 7-8 year-old girl carrying a 20-litre jerrycan of water.

Roofs are used as pasture

The village Buddhist temple

The village shop

We come across a caravan of goats travelling between Nepal and Tibet.

The caravan comes down from Tibet with salt and then goes back up with rice…. an essential barter.

Our caravan of yaks climbs towards the next camp, which will be set up near the Karnali river.

26th September

The day before we lost a yak.

So today : Jacques scolds the yakmen and orders them to form 6 groups of yaks walking at a respectable distance from each other. The loads carried on the yaks’ backs suffer less.

We return to the right bank of the river

and climb about 500m to the village of Kangalgaon.

We have lunch at the entrance to the village, surrounded by children.

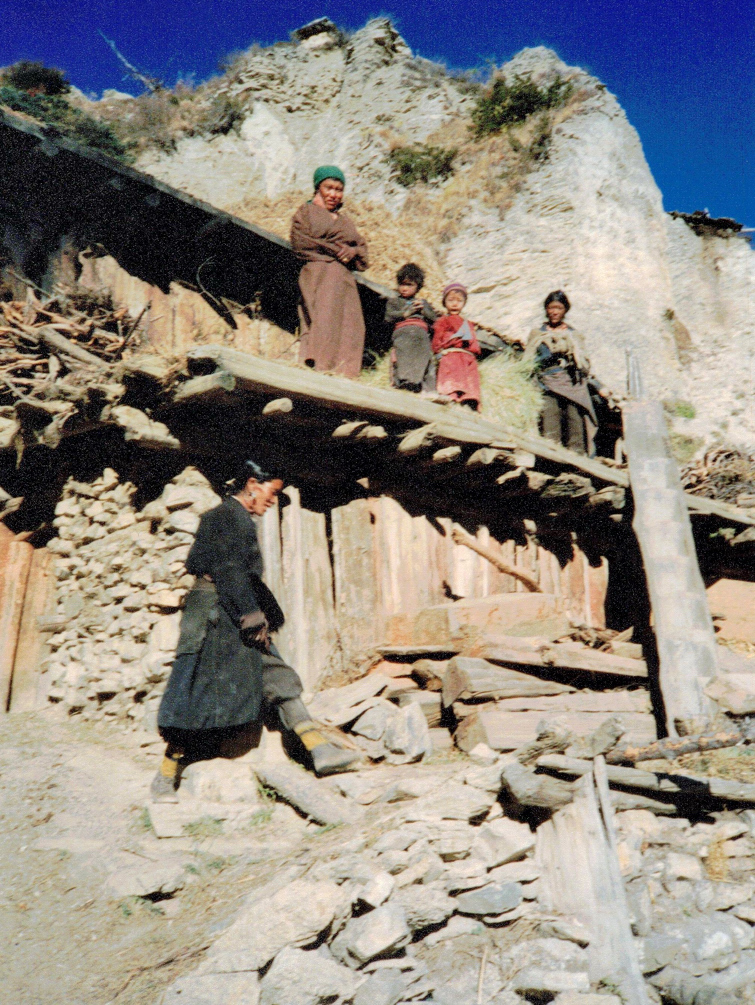

Once in the village, we are warmly welcomed and invited to climb onto the roofs of the houses.

Jacques tells us that the people living there

haven’t seen a white person for five years.

An (almost) cxomplete wash in a torrent

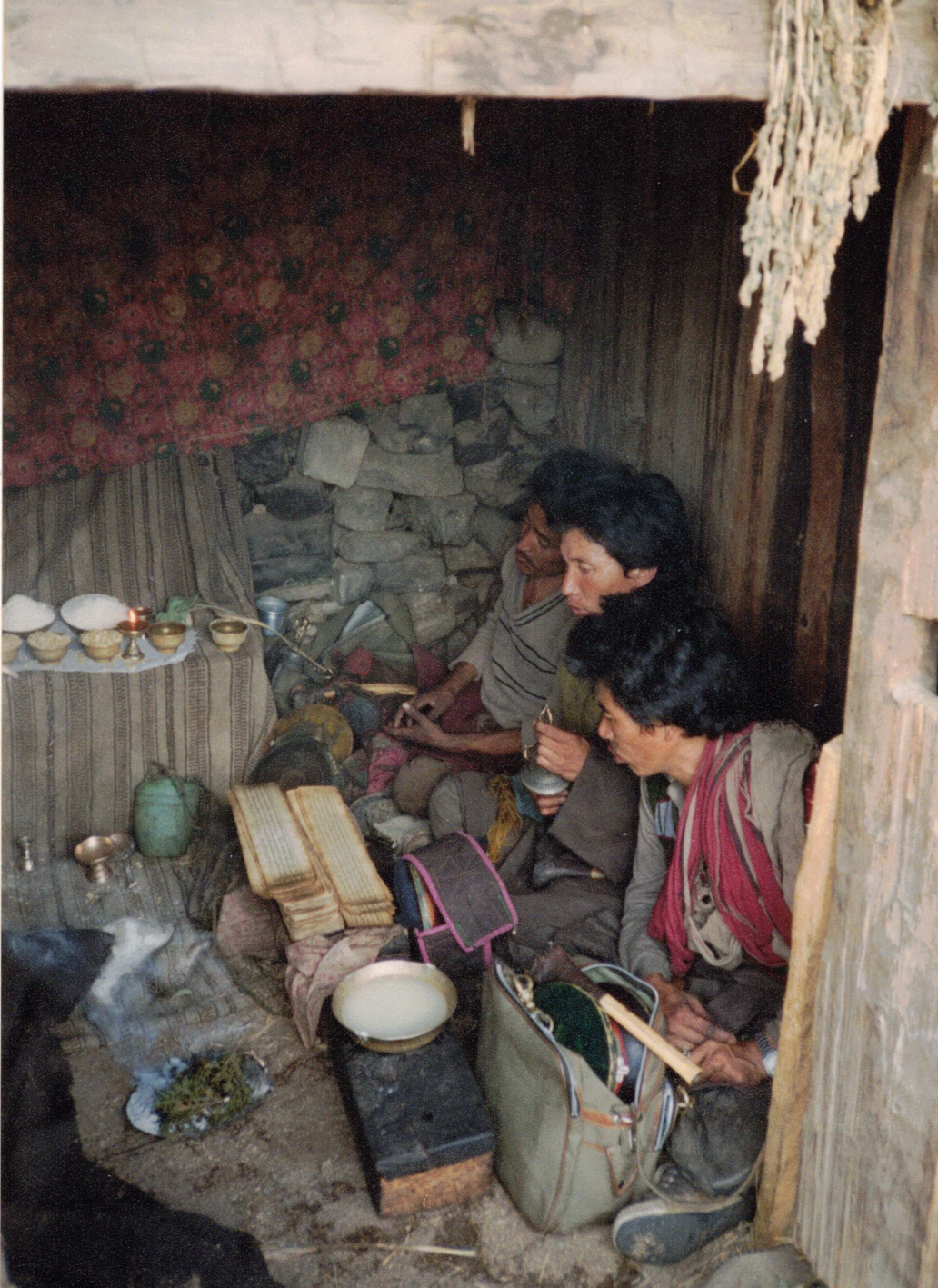

We are also invited to attend a religious ceremony in a small room.

A tough climb to reach our camp tonight

A young yakman

We finally reach Jumla,

after crossing the Jumlakolagna pass.

During the ceremony, the officiants played the trumpet,

carved from a human tibia.

27th September

The Jumla camp has been renamed the « camp of the snake and the two eagles ».

Georges woke up with a superb viper in his tent, curled up some 30 cm from his head.

Last night, as in previous nights, it rained. This morning the weather is fine.

As we leave the forest, we are greeted by three Tibetan women living under canvas and branches.

They offer us Gorgour Tchaï and whey. We give them red chillies in exchange.

Meals and ablutions

on the banks of a charming lake.

The climb to the Chhotelagna pass is a long one. Geneviève and I are behind. I follow the tracks and use my binoculars to spot Georges, who appears from time to time in the distance.

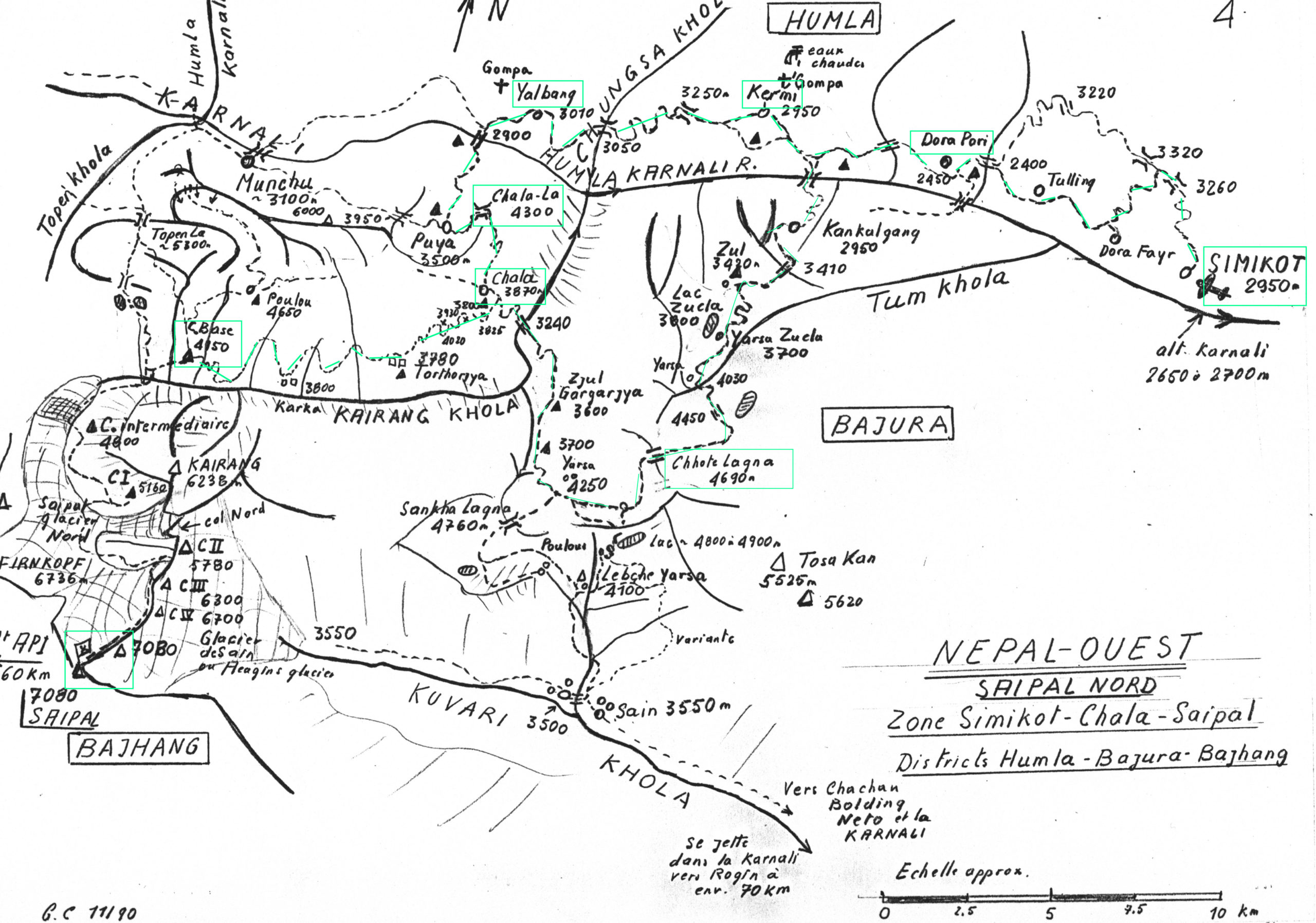

We reached the pass at 4690m. The descent is vertiginous. We reach the camp at dusk. Shanka Lama helps us carve out the terraces for our tents.

28th September

In the morning I discover that the bottle of shampoo has opened in my toilet bag…. Everything has been washed, except my hair.

The weather is fine. A tough descent to the bridge over the Kairang Khola. We pass near Chala and make the long crossing to Tothorya.

We pass some hay carriers…

…and two women shelling buckwheat with their feet.

The lost yak has returned… but without its load!

29th September

The liaison officer fasts until 10.15am and then organises a small ceremony to celebrate the Dashain. The Dashain is the biggest festival celebrated in Nepal. The festival lasts around 15 days. After the ceremony, we set off again for the last stage, the one that will take us to the base camp, where the progress becomes trickier, especially for the yaks. At one point, the sherpas had to cut a path about thirty centimetres into the side of the moraine. We have a picnic by a stream under birch trees. The base camp is reached around 3.30pm.

Everyone prepares a spot for their tent.

I carve out a platform with the ice axe,

and prop it up with a few large stones.

30th September

Daybreak is at 8am. The yakmen are paid and we give them each a packet of cigarettes. They leave the camp with all the animals and we suddenly feel isolated in the middle of the Himalayas. Everyone goes about their business: washing, writing letters, arranging things…

Geneviève, the nurse, provides some care.

I myself am being treated for a small infection in my left index finger.

Base camp (4150 m) and ascent

1st October

At 7:30 a Sherpa brings us a cup of tea in the tent. A pleasant tradition that I have enjoyed on all my expeditions and treks in Nepal. A hearty breakfast in the mess tent: omelettes, Paratha pancakes and tsampa (toasted flour), accompanied by tea.

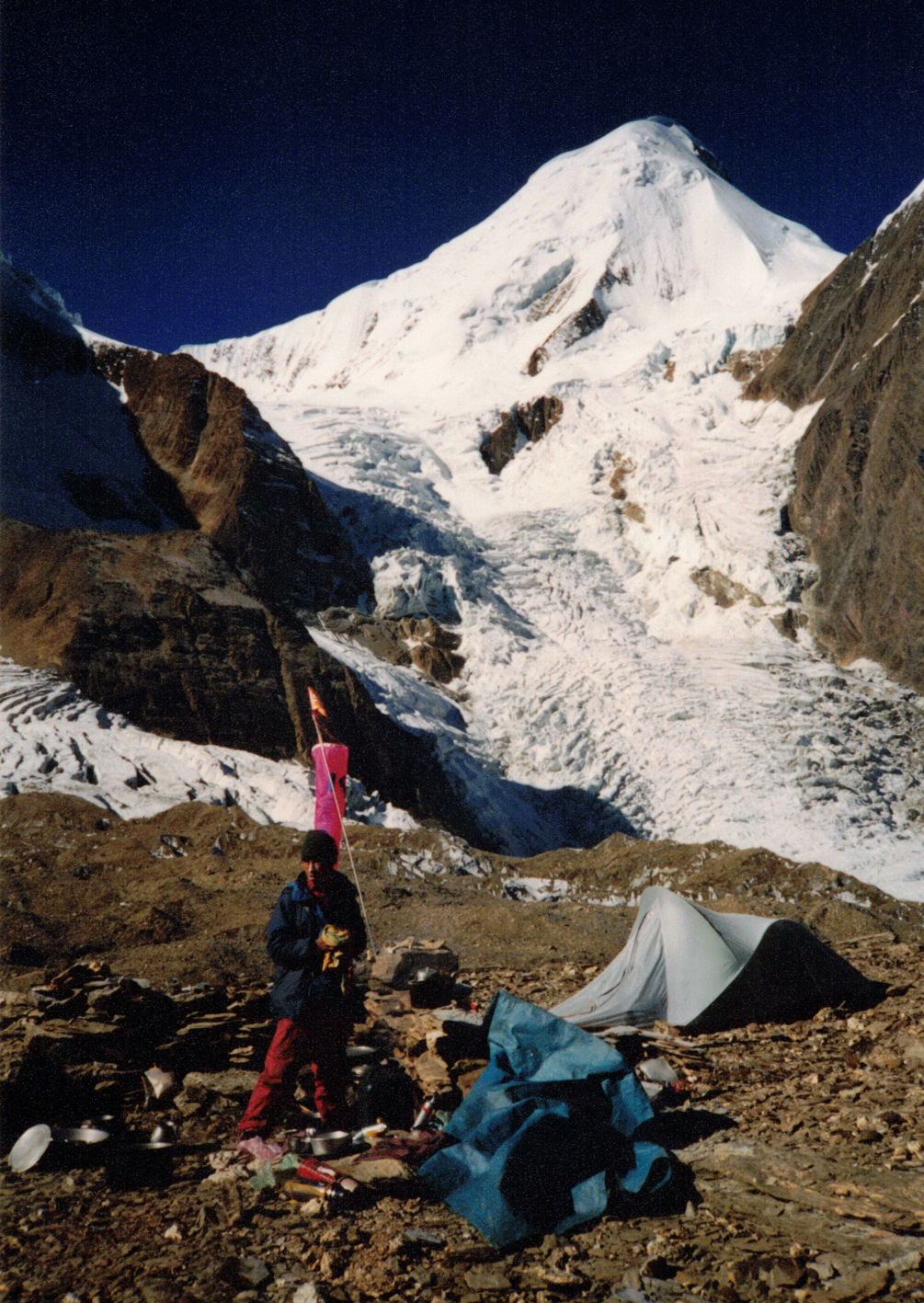

At 10am, the Nepalese hold a ceremony to ward off fate and appease the mountain gods (Himalaya = mountain of the gods). They set up a small altar and hang small squares of cloth, in 5 different colours (representing the 5 elements), over the camp. These are the prayer flags.

The afternoon is devoted to preparing the equipment for the altitude and building the two pillars of the bridge by assembling large blocks of stone.

The next day, these pillars will be connected by a beam from the kitchen.

Prayer flags are small rectangular pieces of coloured and printed cloth, hung from mountain passes, mountain tops, crossroads, house roofs, bridges and outside temples.

According to the followers of Tibetan Buddhism, the wind that blows, caressing the sacred printed formulas as it passes, scatters them in space and transmits them to the gods and to all those it touches in its path.

2nd October

During the night the temperature dropped and the snow appeared at around 4500m.

We start assembling equipment at the intermediate camp (4800m). Tents, food, wood for cooking and the technical equipment needed for the ascent of Saipal.

Along the way, we build cairns on the scree and moraine to help us find our way in case of fog.

A long climb with a particularly heavy rucksack. Our ankles were aching. The fatigue and cold upset my digestive functions. I was ill, and the night was restless with vomiting and diarrhoea.

3rd October

I’m not up to the task and stay at base camp with Geneviève and Georges. The others go back up to spend the night at the intermediate camp and continue with the installation of camp I at 5200m.

Notre objectif se précise

Intermediate camp

4th October

I’m feeling better. The weather is fine but cold. I head north with Geneviève and Georges for a possible ascent, then leave them to climb one of the neighbouring peaks. The rock is so rotten that I have to give up at 4900m. The same day, a Sherpa accompanied by the cook’s assistant and two porters went up to Camp I with equipment and supplies. We kept three porters from Shala for a few days to supply Camp I with wood and food. Geneviève had prepared medicine units with explanatory notes for each of the upper camps.

Shifts (communications with walkie-talkies at fixed times) between the base camp and the following camps take place at 12pm and 6pm and work very well.

5th October

Fine weather. I decide to make a portage to the intermediate camp and come back down the same day. Departure at 9.30 am, arrival at 1.30 pm. Alex and Christophe are here, the others at camp I. Back at base camp at 4.30pm.

6th October

A long caravan leaves the base camp. Geneviève, Georges, Pimba the cook, three porters and me. We reach the intermediate camp at around 1.30pm. Here we meet three sherpas. After a moment’s hesitation, we decided to continue on to Camp I. It was a mistake. Camp I was still short of food. What’s more, the only porter who had gone on abandoned him at the foot of the crumbling gully that leads above the moraine. As a result, neither wood nor cooking utensils had arrived at Camp I. We took refuge in the mess tent and had a picnic with what we could find.

The same day, Gaston, Jacques and two sherpas set up Camp II at around 5800m.

7th October

I decide to go back down to the intermediate camp. I take a packet of biscuits and leave Camp I around midday. Arrived at the bottom: nobody. Vacation with Alex at 2pm, then 4pm, then 5pm. Still no-one there. Strong south wind. I fetch water from a pond on the glacier and disinfect it. On the menu: dried beans, local noodles and half the biscuits.

8th October

Wake-up at 6.30am. Breakfast with hot fruit juice and the rest of the biscuits. The two sherpas and Pemba arrive at 7.30am. We head back up to Camp I, except that they get there an hour before I do! The route on the glacier is in the shade, over pebbles and broken rocks festooned with frost and slippery in places. When I stopped for the 9 a.m. session, a frightful cracking of the glacier sounded beneath my feet. I pack everything up quickly and head for the moraine as fast as the twenty kilos in my rucksack will allow. I arrived at Camp I at around 10.30am. The four climbers had gone to equip camp II, sleep there and the next day set up the tents in camp III. The sherpas eat and then set up the equipment at camp II.

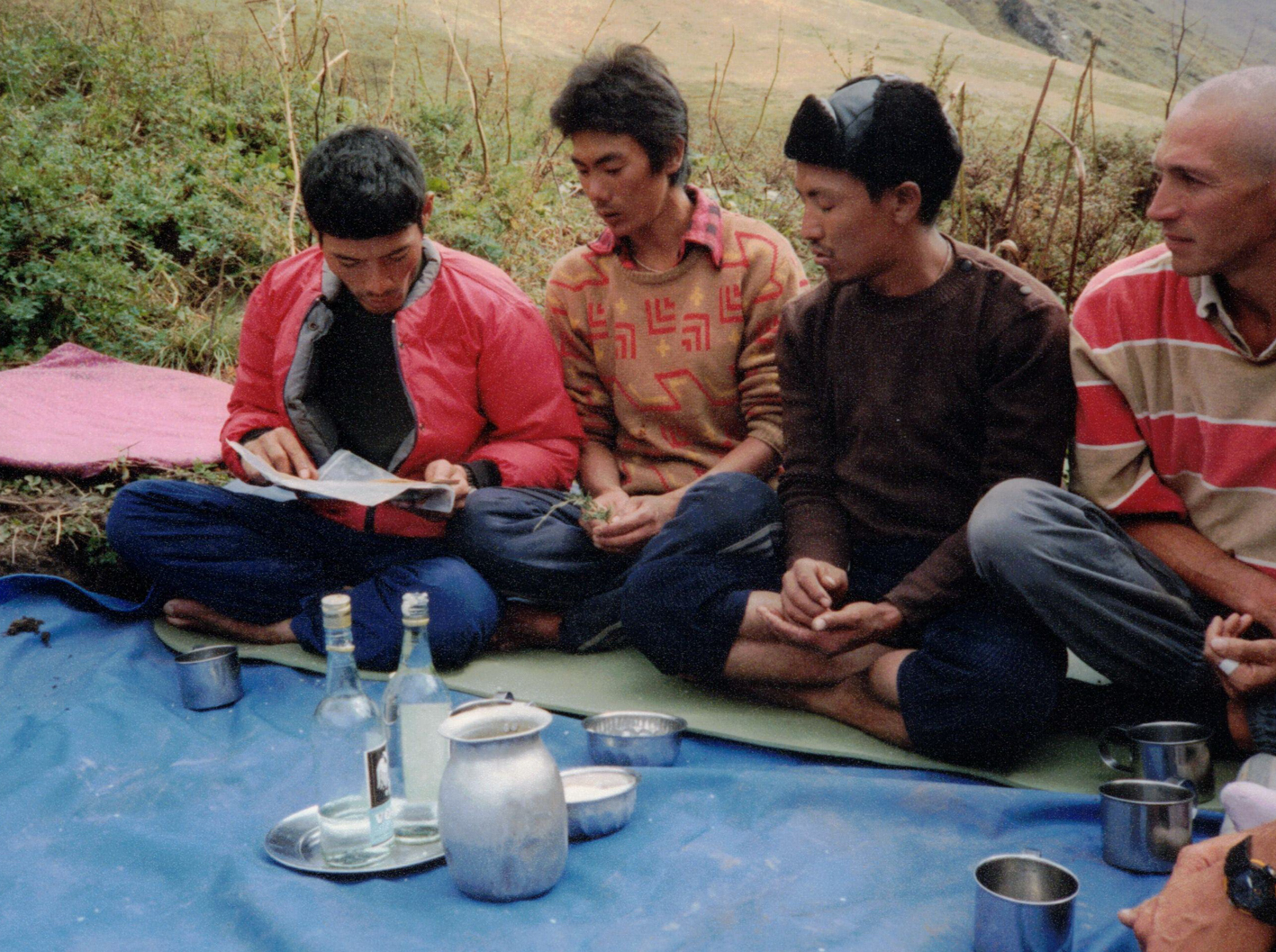

The evening of 9 October

Seven of us huddle together in the mess tent, which sleeps three or four people. It was a very pleasant evening, shared with the Sherpas for the first time on the expedition.

10th October

The Sherpas return to Camp II with equipment. At 10:30 Geneviève, Georges and I also set off for Camp II. We descend onto the glacier, skirt around the base of the moraine and climb up the valley behind it. At one point, I turned left to follow the spur, but Geneviève and Georges didn’t follow me. As it turned out, they had found themselves in some difficult and dangerous passages. We’ll pick them up on the way down.

I leave the spur and make a tricky traverse to reach a snowy flat. The last 100m below camp II are tricky to negotiate. Here I meet up with three sherpas. It’s now 1pm.

We watch our four colleagues, divided into two roped parties of two, attacking the snow wall towards Camp III. We were surprised that they had left so late. After a while, Christophe leaves his party and heads back down. He’ll be back at Camp I with the whole team. It’s 2.15pm and I’m back at Camp I.

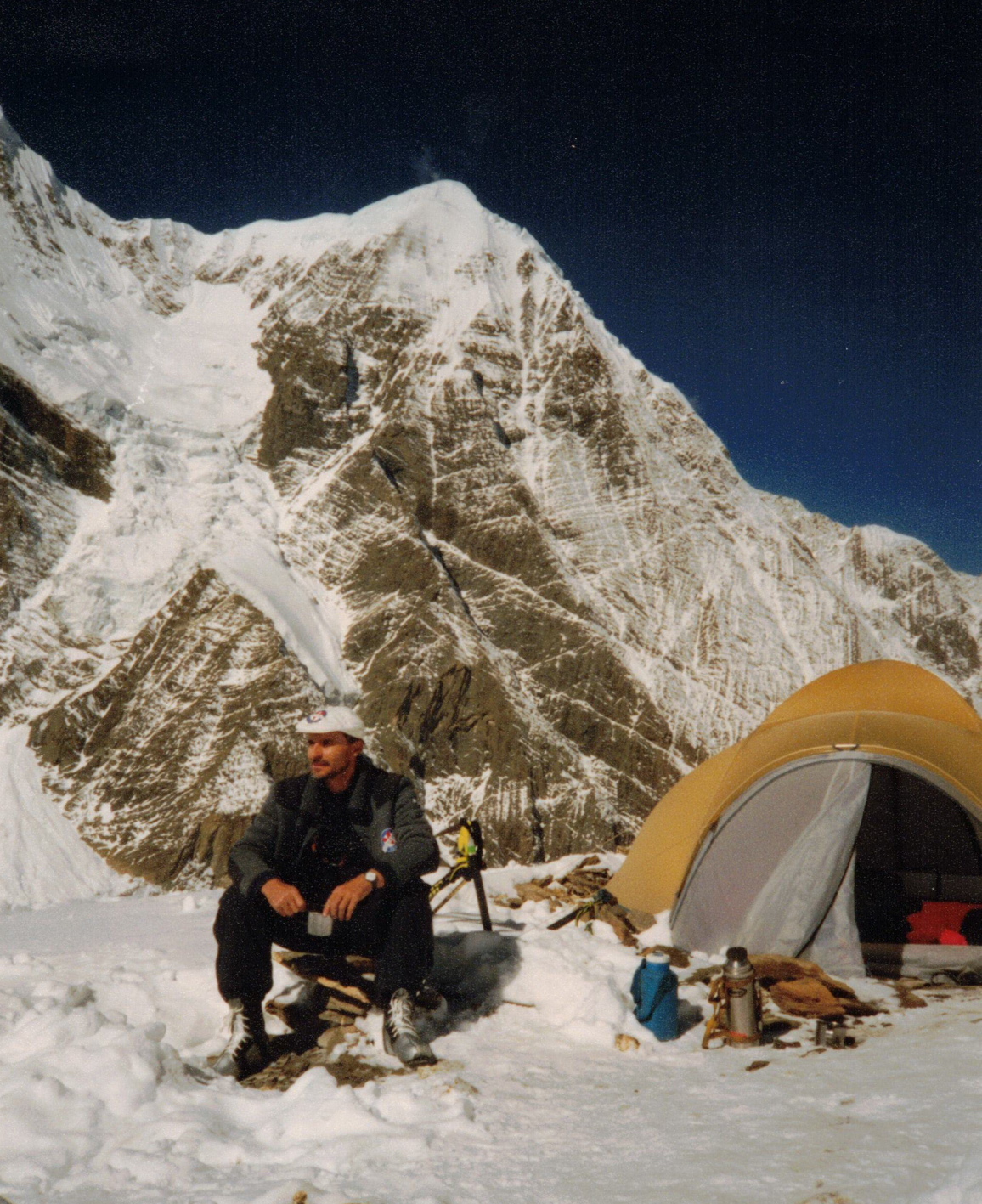

The author of the story at Camp I (5200m)

Saipal seen from camp I

Ringi, who went down to the depot this morning to get some wood, still hasn’t returned. He was also supposed to bring up my high-altitude equipment. But I’ve been wondering for some time whether I’d really have any use for it. I’m not in winning spirits. Today, the lead team equipped the snow triangle that gives access to the summit ridge.

11th October

We look through binoculars at five climbers heading towards the snow slope that leads to the summit of the antécime. Below them, we see Christophe climbing to join them. This group of six climbers reached the flat area at the foot of the second triangular projection and then descended. We hear on the radio that they are missing some fixed ropes. Alex and two sherpas return to camp I.

12th October

The three climbers from camp II set off on another attempt to set up camp III. It’s 4.15pm and they’re just one pitch from the summit of « Pointe de l’Aigle Blanc ».

After some thought, Alex decides to climb tomorrow with the two sherpas and all the technical equipment still in Camp I.

An Austrian expedition, which had arrived a few days before and wanted to redo the route we were in the process of opening, agreed to supply us with the fixed ropes we needed. With this gesture, the Austrians acknowledge that they are going to benefit from the work that the Geneva Section has done so far.

I lend my crampons to Danou – the sirdar – who has broken a strap on his. At the evening session we learn that camp III has been set up on the ridge.

13th October

During the night it began to snow and this morning it is still snowing. The whole mountain range is covered in cloud. The conditions are getting worse fast.

We ask the climbers in camp III to retreat as quickly as possible. We don’t know how long the storm will last. They only have food and gas for two or three days. Dusk arrives. The snow is getting heavier and the layer at Camp I is increasing rapidly. Up there at 6200 m, there is now between 80 and 100 cm of snow. Our anxiety is growing faster than the snow. At Camp I, we’re wondering how long we can hold out before the avalanche danger cuts off our retreat to the lower camps.

14th October

Suddenly the wind drops and we can no longer hear the flakes crackling on the canvas. I slip my nose outside and see a starry sky. The relief is enormous. The sun at 8.30am confirmed the return of the good weather… but for how long? The altimeter showed a pressure drop of 70 metres.

Camp III was finally evacuated, but the two tents remained in place. Our companions made difficult progress in 1 m of powder snow. It’s 11.30am and they should soon be starting down the face.

At Camp I, we burn what’s left of the wood, but eat well. At the end of the day Ringi should be bringing up wood and some provisions. The 70 m of pressure drop was recovered around midday.

By 3pm our friends are at camp III. At 5pm Passang and Ringi arrive at camp I with wood and provisions. That evening, Danou, the sirdar, suggested an ascent strategy that Alex and I thought was a good idea. The following day, 15 October, Alex and two Sherpas climb to Camp II. Those from Camp II descend to the lower camp. On the 16th, Alex rigged the entire wall with fixed ropes and went back down. On the 17th, Alex climbs to camp III, and those from camp I also climb to camp III directly using the fixed ropes. On 18 and 19 October, attempts were made to reach the summit.

Vacation at Camp I

15th October

This morning it’s -10°C in the tent. As soon as the sun came out, the temperature rose rapidly.

At 11am I leave camp I to go to base camp.

I’m nostalgic to be leaving this place forever « without imagining that I’d be back here 6 years later ». I look back several times and take photos.

I arrived at the base camp at around 4.30pm under a threatening sky. Geneviève and Georges had gone up to set up a mini-camp 400m above us on the site of an old sheepfold, now in ruins.

In the evening, the liaison officer and I are alone.

We have dinner together in the base camp kitchen.

16th October

I pack a bag with the last of the high altitude rations for Pasang and Shanka to take up. I give Shanka my winter boots. He has to pay 4000 Rps for the ones he damaged. I feel sorry for him, knowing that he sells a kilo of rice for between 4 and 5 rupees, and a kilo of bread-making grain for between 3 and 4 rupees. What’s more, his 13-year-old son’s school fees cost him 450 Rps a month and his 11-year-old daughter’s 350 Rps a month. Shanka works six months a year as a high altitude Sherpa, takes two months off and then works for four months on her land.

While the cost of employing Nepalese may not seem very high to us Swiss, the income they earn from a season’s expedition is substantial. It enables them to support their families and, above all, send their children to school. Those of us who claim that we shamelessly exploit Nepalese staff know little about the reality on the ground.

17th October

Pema has just left for Chala to bring back the yaks for our return to Simikot. His mission is also to bring back a sheep to celebrate the end of our stay at base camp and, I hope, the success of the climb. I gave him 1000 Rps for this. The price of a sheep should be between 700 and 800 Rps.

I’m in the tent, standing in a basin of hot water with the intention of washing my lower body (yesterday I’d washed my upper body), when Passang arrives with a letter from Gaston asking for wood, milk, sugar, batteries and toilet paper. Passang left the same day with the groceries. We dine by the kitchen fireplace by the light of a paraffin candle. A wick of double-twisted toilet paper dipped in paraffin, with one end sticking out through a hole in the centre of the iron lid of a glass jar.

18th October

Overcast and cold wind. I leave the camp heading NNE to join Geneviève and Georges in their camp. We have a picnic together and I help them bring down some equipment for the base camp. Message from Gaston again asking for food and medicine for Christophe, who is suffering from angina. He also tells us that the climb could last until 21-22 October, although the yaks were ordered for the 20th. Council of war. Finally, one of the Nepalese from the Austrian expedition goes to Chala tomorrow to delay the yaks until the 23rd. Passang makes a portage to Camp I.

19th October

The washing is hanging from the prayer flags. Georges brings me two books and I lend him mine. As is the case every late afternoon, the sun disappears around 4.30pm and the temperature immediately drops by around ten degrees in the space of a few minutes. I put on tights, overtrousers, a down jacket and a hat and put my feet up in my sleeping bag while I waited for supper. Meditations, dreams and projects fill my mind.

20th October

We leave the camp at 10.30am to head north up the torrent valley. The weather is very fine. The scent of plants wafts through the air with every step we take. A gentle breeze soothes the heat of the sun. The slopes are covered with juniper trees that form green patches on a carpet of yellow, ochre and russet vegetation. We reach a small, partly frozen lake at 5,200m. Suddenly, through binoculars, we spot a group of Tibetans on a ridge some 300m away. As I walk towards them, they get up and leave. I continued on, hoping to find a trail…

… There weren’t any, but I was surprised to see a whole family arrive. They were even more surprised than I was, especially to see a white man there.

We find out later that they passed close to the camp, carefully avoiding it. They were Tibetans who had avoided the Muchu checkpoint to enter Nepal illegally.

Back at camp we see the yaks and an old goat, although I had paid for a sheep. I made my dissatisfaction known. I find out in the evening that the goat cost 950 Rps; it’s much too expensive and I feel I’ve been cheated.

21st October

I reiterate my dissatisfaction to Pokharel. He tells me that the goat will be bought back, half by the Austrians and half by our sirdar and cook, and once in Chala a sheep will be provided as requested.

Around 3.30pm our climbers reach the base camp. The goat’s throat has been slit and the meat butchered, ending up in momos, which I don’t eat. We plan our return route, with 14 days left as the flight from Simikot is scheduled for 6 or 8 November. Gaston and Jacques tell us about a plan to make another attempt towards the summit of Saipal in 4-5 days, while the rest of us go to Saïna. The two groups would meet at Chala around 30 October.

22nd October

Gaston and Jacques decide to try again. We take stock of the food. We’ll have to ration out sugar, muesli and oatmeal. The plan is to buy 40 kilos of potatoes, 25 kilos of flour, green radishes and dri butter (female yak) from Chala.

The Austrians ask us to take their two trekkers with us as far as Saïna. We agree on condition that the trekkers take their own food. They offer us a bottle of kirsch.

23rd October

It had been decided the day before that half the food and all the mountain gear would be dropped off at Chala and picked up there on our return from Saïna. We had a hard time convincing the liaison officer to go to Saïna, as this was not on our trekking permit. Seeing his reluctance, but knowing that he can’t wait to get back to Kathmandu, we get him to let us go to Saïna and in return we agree to waive all claims if he gets to the capital before us.

The yakmen, who have been here since 20 October, are getting impatient.

As usual, Georges complains about the inefficiency of the Nepalese. The camp is dismantled and the yaks are loaded in great disorder.

The day before, Gaston and Jacques put aside enough food for four days. Tonight our two mountaineers and the sherpas Tendi and Ringi will have dinner and spend the night with the Austrians.

We finally leave the base camp at 11.15am!

The plan was to stop at the grassy saddle an hour from Shala. But on the pretext that there was neither water nor wood there, the cook dragged us all the way to Shala, all because he was too lazy to go down ten minutes to fetch water and five minutes to fetch wood. Finally, just as it was starting to get dark, we reached a flat spot on the left buttress of a gorge that separated us from the village. We had been walking for almost six hours. After some rapid descents and tough climbs, we had only lost 300 m in altitude compared to the base camp.

Geneviève was in charge of rationing the sugar, as we only had three kilos left for fourteen days. Sugar is very scarce in the region, so we can’t buy any.

The return

24th October

A rest day devoted to visiting the village and the surrounding area. Shala has some thirty families, ranging in size from four to twelve people; that’s around two hundred souls. A woman can have up to six husbands, but only one stays at home for six months to a year. The others leave either with the herds or to do odd jobs in other valleys further south.

Alex and Christophe go paragliding. We follow them with binoculars. After a few unsuccessful attempts, they’re off! The colourful sails swell and the villagers open their eyes in wonder. In the afternoon, Geneviève (carrying a rucksack full of medicines and medical equipment), Georges and I set off to meet the locals.

Geneviève provides care and hands out a few trinkets to the village children.

Some are posing, others are working in accordance with the local custom based on a subsistence economy.

The roofs of adobe houses are flat. In fine weather, these roofs are used to dry cereals. In this region with its harsh climate, only barley and buckwheat can be grown in the valley bottoms. In winter, when the snow covers everything, the inhabitants move from one house to another via the roofs.

Mail runner

Pema tells us that he’s going to entrust some mail to a « mail runner ».

A Nepalese who can cover long distances quickly to deliver letters and other documents. These people can run for several days while sleeping under the stars. We hasten to write.

We heard from Shanka that the sirdar had decided to leave the tent-mess in the village.

Danou must have sensed the protest because we didn’t see him all evening, busy drinking with Pema and flirting in the village.

25th October

Finally, the tent-mess is folded and loaded onto a yak. The route we took four weeks ago on the outward journey seems even more beautiful. The colours are magnificent. Red bushes, dark green pines, red stubble fields and snow-capped mountains.

The river along which we walk offers a welcome haven of coolness. We stopped there for a good two hours, our feet in the water and our heads in the sun, just like the rice.

Saïna

This is where Chala’s caravan of yaks, returning from the Saïna pastures, meets us.

Some of the young yaks are finding it difficult to cross the ford.

To prevent them from being swept away by the current, some adult yaks stand downstream and offer their bulk as a support to the young ones.

Men, children and even (young) women are happy to take photos. To thank us for giving them an ‘instamatic’ photo, two young girls offer us three handfuls of small balls of very hard cheese to suck on.

After a three-hour walk, we reach the Tothorya mountain pasture.

The yaks with their loads arrived a good hour after us.

Fortunately, Passang came up with the hood from the kitchen,

so we could drink tea while we waited.

26th October

The sound of bells draws me out of the tent. It’s another procession of goats carrying small leather-bottomed jute sacks full of salt on either side of their flanks.

Once the salt has arrived in the south, it will be exchanged for rice, which will head north.

We are at an altitude of 3,650 metres and have to cross a pass, the Chanka-Lagna, at over 4,700 metres.

To give us strength, the cook prepares a « dal bhat » at my request. A dish made with white rice and lentils.

400 m below the pass, we stop at the top of a ridge, near four stone houses that are missing their roofs. Here we meet up with Danou, who has spent the night in Chala drinking Chaang (a type of local beer). The camp is set up on the edge of a vast basin where a branch of the torrent meanders.

.

At 6pm, Gaston tells us that Jacques Montaz, accompanied by Tendi Sherpa,

reached the summit of Saipal at 3:15pm.

The expedition was therefore a success.

The Geneva section of the SAC has opened up a new route in the Himalayas!

Read the story in pdf

27 octobre

Journée consacrée aux lavages en tout genre. Georges, prévoyant, a tendu une corde à linge entre des bâtons de ski. A midi nous partons faire une balade sur l’une des croupes herbeuses qui ceinture le plateau. Un vent glacial souffle du sud et nous voyons le Saipal pris dans la nébulosité. Un aigle tourne au-dessus de nous. Nous apercevons également trois mouflons. Vers le sud-est, la vue s’étend sur plus de 100 km et va buter sur la masse imposante du Kengi Roba.

A quelques 1200 m. en-dessous de nous s’étire la plaine de Saïna. En descendant la crête d’une moraine je tombe sur un replat avec des huttes de bergers de yaks. Constructions basses en pierre, avec une porte comme seule ouverture, sans cheminée, couvertes d’écorce de bouleaux et de pierres plates

28th October

We decide to descend to the Saïna plain to observe the east face of Saipal.

Alex and Christophe decide to come up and join us paragliding.

We see them trying out the inflation system so that they can take off as soon as the wind conditions are favourable. They set off.

Alex descended fairly quickly towards us but a drop in lift 20 m from the ground caused him to miss the landing area and he landed in a swamp.

I rushed over to him to help him lower the sail as the wind on the ground was so strong.

After a snack, we set off on the return trail. Halfway back, I feel myself getting tired from hypoglycaemia. I nibbled on an energy bar and climbed the dreadful goat track back to camp.

Shouts and laughter draw me out of the tent. Christophe is teaching Danou and Shanka how to inflate the sail. The yakmen stand at a distance, not very reassured.

29th October

The moon is in its waning phase and the half-sphere covers the landscape with a silvery glow. It’s 4.30am and I’m out of the duvet for an emergency. Later, Passang’s ‘morning tea’ has a hard time pulling me out of Morpheus’ arms.

After dinner Alex organises a photo shoot for our sponsors.

For Rohner, we hang socks on the wrong side of a yakman’s coat.

He pulls aside the flap and presents us with the goods on the sly!

We decide to leave for Chala tomorrow, a day ahead of schedule. In the evening, Temba sees two lamps coming down from the pass. We immediately think of Gaston and Jacques. It turns out to be Tibetans with two Nepalese guides heading south.

30th October

Partly overcast skies. Georges decides to reach the pass via the ridges. I decide to follow him, avoiding both the dust of the normal route and the company of the obnoxious Austrian liaison officer. We quickly gain altitude, but then waste time zigzagging between dwarf bushes that make the sound of crumpled aluminum underfoot.

At the pass, the wind freezes us and we plunge straight into the 1200 m. descent that awaits us. We inaugurate a new route to avoid the yak trail, which is really steep, overhanging and covered in powdery dust that coats the nostrils and crunches under the teeth.

I arrive at the camp first and enjoy a very long coffee without sugar that Passang had the good idea of preparing. This time the sugar supply is gone. I comfort myself by thinking of the little box of Assugrin that I had had the foresight to slip into my luggage when I left Geneva.

To pitch the tents we battle against a violent wind. As soon as the first sardine was planted, the wind died and the sun came out again.

A few tentative remarks about the weather make me realise that my companions, like me, are wondering whether we’ll be able to escape any snowfall. According to the locals, if there is any snowfall, it shouldn’t be significant. In fact, the real bad weather doesn’t set in until mid-December or even January.

From then on, all life comes to a halt until April. The high-altitude villages gather wood and provisions for their people and animals, so that they can live in the cold for three or four months.

The contribution of an expedition like ours is far from negligible.

A yak rents for 300 Rps, twice the price of a porter, as it carries two loads.

Ten days’ hire therefore earns the owner 3000 Rps, enough to buy an additional yak.

It’s 5pm and it’s getting very cold. Strangely enough, it’s my biros that’s acting as the thermometer: the ink is freezing more and more and it’s starting to stutter. It was time to put on a down jacket and hat. From then on, my life at the camp followed a set pattern.

Writing or reading as long as the fading daylight allows.

As darkness falls, at around 6pm, I close the tent and, by the light of the headlamp, prepare the canteen for the evening’s hot water, the two Aspirin tablets to be taken with supper, the tissues for the night and the earplugs.

That done, I tucked my hands into the shelter of the sleeping bag and waited for the soup to be called.

After the meal, I fill the flask with hot water and place it at the bottom of the bag towards my feet.

I get dressed for the night, light the candle, and enjoy a few squares of chocolate (chocolate bought before departure and stashed in the travel bag). Then I brush my teeth and slip into the sleeping bag, hoping that the abundance of liquid absorbed during supper won’t force me out of the tent more than once during the night.

This evening, the discussion dragged on about whether it was appropriate to send someone to Muchu to try and get our flight from Simikot moving. An exchange of views on the same subject will take place the next day in the presence of Gaston and Jacques. As for me, I share Georges’ point of view that it’s not wise to rush our arrival in Simikot in the hope of gaining one or even two days, with the significant risk of having to spend four days there waiting for the flight.

Like every evening, two campfires glow in the night. The yakmen’s and our cook’s, around which the sherpas gather. While the first is calm and peaceful, the second is full of bursts of voices and laughter.

Yakmen are self-sufficient. They carry their own food and cook in their own corner. Cereal cakes, toasted cereals, sometimes a little rice, all accompanied by salted dri butter tea.

31st October

Once again, the sherpas spread out the breakfast tarpaulin in the shade, while the grass is still covered in frost. A few metres away, the sun is already warming the meadow. I ask them to move the canvas. It’s curious to see the extent to which they lack notions of simple comfort, not to mention general organisation. The same remarks apply to respect for equipment and foresight. They act as if the present were the ultimate moment and that the past did not exist.

We left at 10.30am and arrived in Chala at 1pm. Along the way, Georges had the chance to scuffle in the dust like a sparrow. We caught him at the river washing off the dust that covered him from head to toe.

As promised, the mutton was there. It was gutted, skinned and quartered. It will be transported the next day in a jute bag to Pouilla.

That’s where we’ll be celebrating the success of the expedition.

Finally, in the early evening, Gaston and Jacques return to camp to much applause and congratulations for having reached the summit of Saipal.

To celebrate, the cook prepares a chocolate cake.

East face of Saipal

view from Saïna

Pokharel sends a messenger to Muchu so that the local police station can inform the ministry, the police and Pabil Treks (all three in Kathmandu) of the success of the expedition.

For his part, Danou sends a messenger to Simikot to confirm our flight to Nepalganj. His mission is also to bring back some food for the end of the trek. He should meet us at Kermi, our next stop.

The latest news is that the King of Nepal has been summoned to endorse the latest constitution. If he doesn’t, we fear unrest.

Pokharel reassures us that foreigners are in no danger.

1er novembre

Nous traînons un peu car le chemin jusqu’à Pouilla n’est pas long. Alors qu’à 11h. Danou et les yaks ne sont toujours pas là, Georges se fâche et part pour les débusquer. Le sirdar se fait houspiller. Il rejoint le camp tout penaud et un peu pompette.

Pokharel et moi sommes invités, par le seul adolescent qui ait obtenu l’équivalent de notre certificat d’études à venir visiter sa maison.

From alleyways to terraces, we arrive at a relatively well-to-do house.

It is built on two floors. On the ground floor are the animals, on the first floor, reached by a tree trunk with steps cut into it, there is a small room, a lean-to and the main room.

The main room is very dark, as only a small opening in the ceiling lets in a little daylight. This opening also serves as a fireplace.

The centre of the main room is occupied by an open fireplace.

There is a low bench on one wall and shelves on another. Jars hold water.

All the walls and ceiling are black with smoke.

The mother sits cross-legged by the fire, nursing the youngest of nine children. She serves her husband, who occupies the best seat.

We are offered whey and Tibetan tea in small Chinese earthenware bowls, a sign of a certain affluence. We are offered a taste of a buckwheat cake obtained from a neighbouring village in exchange for salt. It comes from nearby Tibet, two days’ walk away.

We learn that the village has 362 inhabitants, 36 families and around 500 yaks. We also learn that the eldest son, who is fifteen years old and has the certificate, will be married in a few days’ time to a girl from the village following a series of negotiations between the two families.

As usual, Geneviève was surrounded by adults and children looking for care and toys.

Meanwhile, Christophe flew over the village in his paraglider, creating sensation, amazement and sometimes fear.

We continue towards the pass at 4300m.

After a break, we plunge down towards Pouilla.

This hamlet of a few houses is already deserted for the winter and lies at the bottom of the valley where the Karnali flows 700m below.

From here there are two tracks. One goes up towards Muchu, a village on the border with Tibet, while the other follows the river towards Kermi.

We pitch our tents on the site of two freshly cut cereal fields.

The yaks arrive shortly afterwards. We learn that one of the animals has lost its footing on the descent and that its load has tumbled down the slope, lost among the pines and rhododendrons that cover the mountainside. Tomorrow the yakmen will try to find the luggage.

Once again, we celebrate the ascent of Saipal by uncorking a good bottle of whisky bought by Alex during our stopover in Frankfurt. Given the late hour, it was decided to grill the mutton for dinner the next day. The meat is hung from the mas of the mess tent to protect it from predators.

Gaston, who had celebrated the company’s success with dignity the day before, had a yellowish complexion and settled for a « Saipal tea ».

2 novembre

Geneviève and Georges prepare the pieces of meat.

The meat is cleaned, brushed with oil, massaged with aromatic herbs, truffled with garlic and…

…injected with whisky (to sanitise?).

Shanka digs a rectangular hole into which he places the egg crate that we will use as a grill and lights a large fire to make the embers. We enjoy a delicious mutton dish with potatoes in field dress.

It was decided to make a list of the equipment that each of us was prepared to offer to the Nepalese staff, and a certain amount of money would be set aside to reward our liaison officer for his cooperation and courtesy.

I also learn that a kilo of meat sells for around 70 Rps. Given that the sheep gave us thirteen kilos of meat, the 1000 Rps (about CHF 8.-) paid for the animal seems about right.

We had a light supper. An hour after our meal, the cook invites us to tea. « I hope there will be biscuits » I said jokingly. It wasn’t a joke, just a reflection of my knowledge of the habits and customs of the Nepalese people.

The evening was enlivened by a lively but courteous exchange of views between Geneviève and Jacques on the respective qualities of Eastern and Western medicines. It’s a full moon tonight and the atmosphere is magical.

3rd November

We wake up at 7am, an hour and a half before the sun. It’s very difficult to get out of the sleeping bag. It’s going to be a long day, so we have to leave early. The yaks leave at 9am and we leave at 9.30am. We overtake them shortly afterwards.

The descent to the Karnali river is superb.

From Yalbang to Kermi, the trail is just as beautiful.

New species of trees appear. Wild walnut and apricot trees.

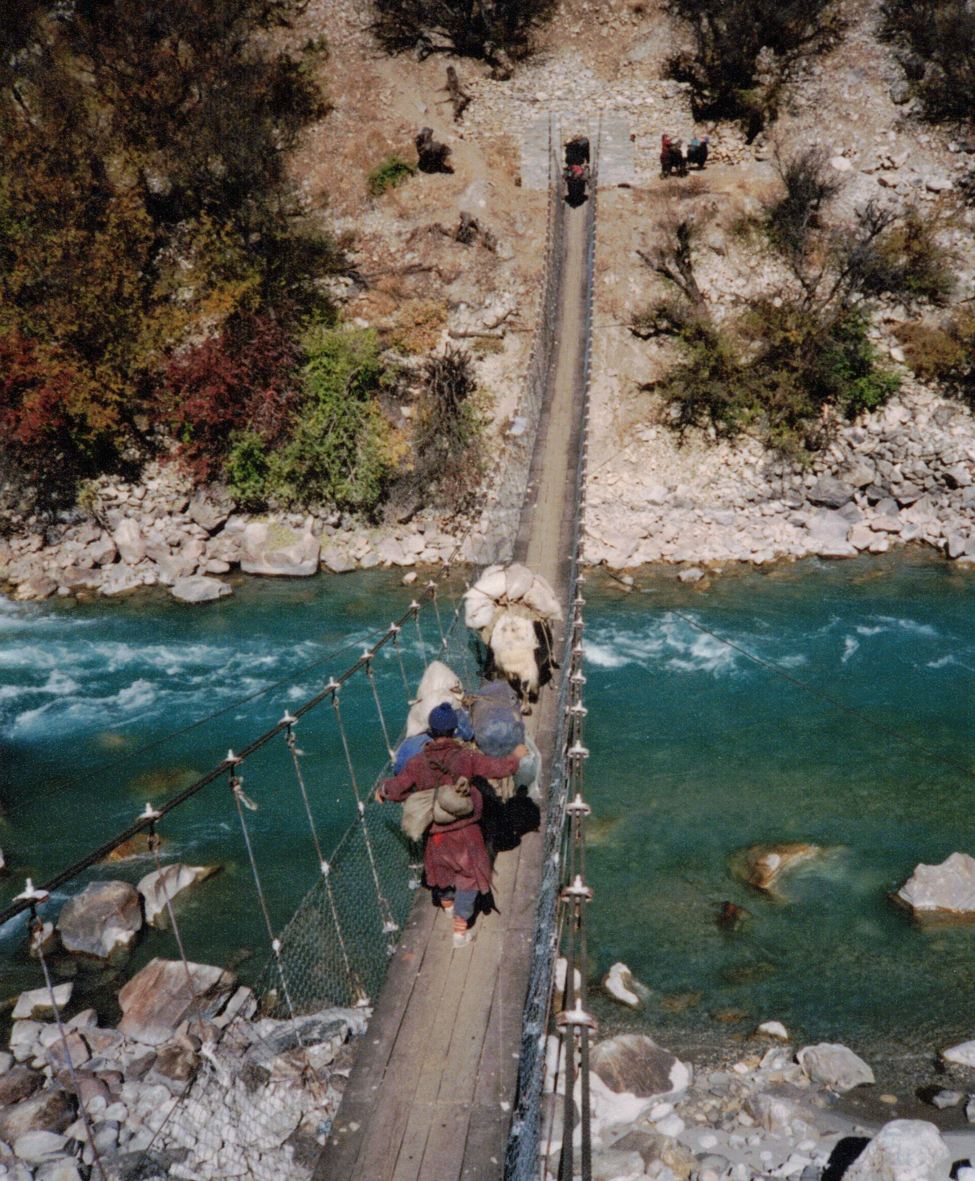

Only two anchors remain from the old bridge.

It has been replaced by a suspension bridge above the river.

This is one of the most hilarious episodes of our trek.

The yaks, afraid of this moving footbridge, refuse to use it. The yakmen have to work in fours to get an animal across. It was a real battle between man and animal.

One of the yaks, seeing this confrontation, escapes from the vigilance and jumps into the water with all his gear. It swam, fought against the current and finally managed to get a foothold on the other bank. The luggage took on water, including my equipment bag.

On the way up to Yalbang, at the bend in the path, we come across a water mill and a nice surprise. It houses a young miller grinding grain.

In the village we are greeted by Pema, who introduces us to his wife.

As in every village we pass through, Geneviève provides medical care.

After a lunch break, we begin the key passage along a path cut into the rock face.

Two years ago, the yaks had to be unloaded before they could cross.

This time it wasn’t necessary, as the passage has been improved.

Then we meet a one-eyed child who offers us some nuts. Gaston gives him a notebook and a pencil. The boy is immediately adopted and nicknamed « Vendredi ». He won’t let go of his notebook until Kermi.

At the fork in the road, Gaston turns left towards Kermi to visit a lama (religious leader) and, more importantly, his younger sister! We don’t see him again for the rest of the evening.

Georges and I continue on our way to Dara Pori, looking for a place to set up camp. Ringi is there too. He had returned the same day from Simikot after a six-hour walk, bringing us three kilos of sugar and certifying that he had sent the telegram requesting that the day of our flight be brought forward.

However, we are very sceptical about the result. The company that manages domestic flights in Nepal is called ARNAC (ARNAC in French means scam).

4th November

The Kermi camp is well positioned and the sun is already warming us up at 7am. Given the heat during the day (25°C), the Chala yakmen don’t want to go any further as their animals can’t stand these temperatures.

We managed to get three horses and a few dzos (a male hybrid of a yak and a cow) from Kermi. At the same time, the yakmen of Chala managed to sell their wooden bowls and a few ropes made of yak hair to Alex and Christophe, who thought they had made a good deal.

On the way we passed quite a few people. This route seems very busy. A stop at a hostel (wooden hut) allowed Christophe to offer Georges and me a cup of milk tea for three rupees (tourist price).

All day long we followed the Karnali. A little before Dara Pori (Dara = spring and Pori = behind) we passed the bridge that had enabled us to cross the river on the outward journey, so we knew we had come full circle. A short stop at Dara Pori where a local sells us apples at 1 Rps each. We then followed the paths to a tributary of the Karnali.

The camp is set up. It’s 4pm and we’re at 2800m.

On a field next to ours, a group of merchants had already set up camp. They’re on their way to Tibet with a load of rice.

We all feel it’s time to end our journey!

Aside from the little niggles that proliferate, we notice that the equipment is getting tired and the clothes, despite being washed a few times in cold water, are starting to absorb the local smell.

The evening news on Radio Kathmandu mentions the success of the expedition

5th November

The ascent to the pass at 3400 m. that leads to Simikot is tedious, but the descent is quick as we can already feel the beer on our lips.

En route, the sherpas have bought two racing hens (it takes an hour to catch the second one).

One evening, we decided to invite our Nepalese staff to a dinner in Kathmandu, during which we would distribute the « gifts » in the form of equipment and clothing.

Finally, we will be leaving Simikot on 8 November.